Continued from Part 1

O’Brien’s future plays into the histrionics of its age, particularly the violence of large scale combat with its massacre, but by the time of John Kelly’s From Out of the City histrionics are of assassinations and terrorism. The texts narrative studies the build-up and fall out from the supposed assassination of the President of the United States on Irish shores. Our narrator, Monk retells the events of one man that have occurred during this time frame, Anton Schroeder. In focusing on this singular individual in the larger narrative events, Kelly is focusing the dystopia away from O’Brien’s individual in a national level dystopia and onto the individual in a globalised dystopia.

This differentiation between Kelly’s text and O’Brien’s comes starkly into conflict with through the bar scene in Liddley’s following a riot at Leinster House which Schroeder has escaped from. In this den of despair Schroeder engages in conversation with Paddy (Patrick) the barman, a Senegal émigré named after the footballer Patrick Vera, as the former gets drunk with a stereotypical Irish gombeen known as Jules Roark, a government informer. Schroeder turns asks Paddy in French, the language of Senegal’s once Colonial rulers, to order a taxi. Paddy responds to him in English however only for Schroeder to respond in turn through Gaelic asking him “why he is being such a shit and he gets no answer at all”. The language common between nations has become English or French, a colonial inheritance. Yet neither man is able to understand each other in their original precolonial tongues. Paddy asking Schroeder to speak in Wolof, the national language of Senegal, not French and Schroeder belittling Paddy through Gaelic. The scene undermines the whole exchange between the two characters in O’Brien’s text for in Kelly’s dystopian landscape there is no escape from Colonial rule. Kelly’s critique on national identity, unlike O’Brien’s where one language dominates another, theorises that a level of understanding can be achieved through dual language expressions incorporating the external (English/French) language with the internal language (Wolof/ Gaelic).

Through small conflicts reported on twenty four seven new channels, Kelly offers an updated interpretation of our future. While pushing the imagined dystopia world eight years into the future he partakes in the restructuring of this Ireland away from a clearly defined dystopian or utopian structure, instead favouring a sardonic belief that our expectations of tomorrow are never met. Monk, our narrator, oversees the entire landscape of Dublin via his technological haven in his attic. For him the future is all too real and all too stale:

“And for Ireland to end up neither utopian nor dystopian seems to me to be the worst outcome of all. Neither one thing nor the other and all we have is some kind of stasis. Slow death. And waste”.

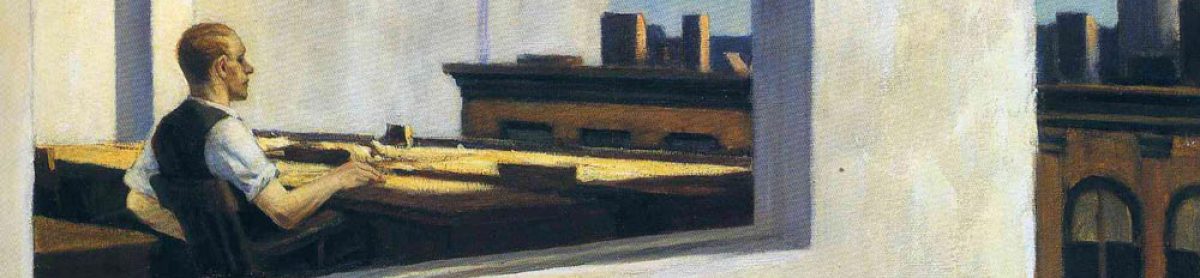

This elderly figure who lives above Schroeder operates like a modern day scribe, fulfilling the ancient position associated with an Irish “monk” as scribes. These records are not manuscript but in the neo-script age upon computers and screens. The role of recording is crucial to the narrative as events begin après midi and launch quickly back into its own relative past; i.e. two weeks prior. Monk’s recording of events are as integral to the overall plot as the national memory found in O’Brien. The difference between the two narratives treatment of memory is that it is treated as a resurfacing of the past within O’Brien’s text while Kelly plays upon the nature of recordings as digitised memory. We receive the narrative through a man’s stored and collected memory after his death. Whereas O’Brien’s text pushes the notion of human memory as a force formed from a national consciousness, Kelly alters this nationalist memory into an external hard-drive.

The relationship memory has to this dystopian genre relies on untangling the temporal interchanges in Kelly’s text. In doing so the past cataclysmic moment that alters this stale future into a dystopia is revealed; the supposed assassination of President King. We receive the assassination information during the prologue which before the narrative flashes back to reveal the lead up to this event. So that Monk can reveal to the reader the true sequence of events leading up to the assassination but here is the kicker, the whole narrative for all its temporal play is a retelling. Monk is living up to his name, he is informing us of a narrative he has inscribed which has already occurred. What Monk has allowed us to witness is the gift of the always live video feed, a complete replay of events as they happened. Kelly’s book differs however from O’Brien in how memory can engage narrative and shows a versatility within the dystopia genre that O’Brien fails to achieve; he is not concerned with the big picture only that of our protagonist Anton Schroeder. The focus of the narrative deals not with the collapse of society into a dystopian model, however much this genre attempts to make its intrusion felt. Schroeder’s escape from the riot outside Dáil Éireann as the Taoiseach’s shades the narrative’s attempts to focus on the man and not the society.

Individuals such as Paula Viola, the reporter and dream woman of Schroeder’s life, help to illuminate Vico’s model that this is the ‘Age of Heroes’ for the dystopia. Society organised via these aristocratic figures comprises the givers of information and controllers of order.

Paula Viola’s role as the television reporter becomes a figure to be worshipped in the eyes of Schroeder. Enacting the Heroic figure in Vico’s language studies, Paula Viola is worshiped by her admirers for her image. She controls and gives information through language and thus operates as a ruler over her viewing and listening subjects. The people trust what she says, they expect the truth. Having Viola appear by the narrative’s end operates as the climax not just the narrative but for Vico’s ‘Age of Heroes’. By presenting herself to Schroeder we can see the façade that this worshipped figure operates behind. She goes from revered reporter and Schroeder’s dream woman to his equal and eventual lesser by her bartering and by accepting his offer of sex in exchange for information. The difference is that at this point Schroeder possess the information, he is inquisitive of her character about how far she will go. The conformation in his living room is not one of lust vs reality but of the ruling class against the plebeians:

-You mean in exchange for sex? Is that what you’re saying? You’d go that low?

-I would. The question is would you?

2 thoughts on “Ireland in the Parallax and Paralysis of Time: How John Kelly and Kevin Barry’s future Dystopias conform and break from Flann O’Brien’s Imagined Tomorrow. Part 2”